Blog

Joe Lambert interviews Marita Jones and Tina Tso from Healthy Native Communities of Shiprock, NM.

Proponents and doomsayers have lined up in the face of the breakthrough of these large language model and deep learning computing engines. How will these developments affect digital storytelling as a community of practices?

Proponents and doomsayers have lined up in the face of the breakthrough of these large language model and deep learning computing engines. How will these developments affect digital storytelling as a community of practices?

My very first interviews were exciting, and people’s reactions were better than I expected: supportive and proud. But after reading those interviews, I realized that I was leaving out important parts of my journey—mainly, the challenges I had faced.

Through this workshop, we learned more about the connection people make between stories and maps, about the process of story mapping, and also about how to use new technology and create trust and a safe space through digital communication tools.

Archive by Month

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2023

- January 2022

- August 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- September 2020

- July 2020

- April 2020

- December 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- May 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- September 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

I remember where I was when I heard the news about our current President-elect making comments about his ability to grab women's crotches without consequence. I remember it because, like so many other women, I’ve experienced this kind of groping, at the hands of an entitled male. For me, it was when I was 12. I'm still wondering how to talk about all of this with my feisty eight-year old daughter.

I remember my first assignment at the Colorado History Museum when I started working in the education department there many years ago. I was twenty-five years-old, recently returned from graduate school in Tucson to my hometown of Denver, and ready to get to work.

In April, staff at the Center held their spring retreat. These retreats happen twice a year, a chance for us to get together so we can talk about the work we do and explore ways we can do it better. With so much to discuss and much at stake, they are as challenging as they are vital.

“I told myself then, 'Never forget this day,'" Mohammed Alyaqubi tells me while I eat dinner with him and his mother, Khalida, my friends who are refugees from Iraq. "I came home from school – I remember what I was wearing. I threw my bag down and the phone rang. ‘Congratulations – on June 11 you have a flight to the U.S.’ We started dancing, turned on the radio, Mom cried."

The place where I worked is no longer there.

I started working in this building when I was 14. It was a shell, we put a floor in, walls, shelves for a gift shop named “Chan & Chee” (for Chandler and Conchita). She was born in the same building. Two years later the steel ball struck the building. Now it’s a county owned garage.

Janet, the rancher I worked for in the late 1990s, called me out of the blue last week . . . Recently I was looking at a photograph I took during that one of those calving season. Why I was looking at this photograph had nothing to do with working at the ranch, but rather to do with my work at CDS, about desire paths, about wanting to be acknowledged and feel enabled. I don’t tell Janet this, although she would have listened deeply. Instead I describe the photograph to her and in doing so tell a story. She remembers…

Our stories focused on the centrality of food to our individual and communal identities. Not surprisingly, everyone had powerful stories to tell about their connections to food, and the initial introductions had us hungry for finding out where this journey would take us, but also just plain hungry as we sampled the best of the nearby Cake Cafe.

First, I have to paint the scene. We were in Bangladesh working with storytellers representing various NGOs from South Asia. Every workshop has interesting twists and challenges- quirky technology keeps you hopping, or stories hold onto you for weeks afterwards, but this workshop was the ultimate opportunity for me to practice presence… in chaos.

Maybe it was the synchronicity. Blue was an unexpected gift from the woman in the bookstore where Marie was passing time, before a doctors appointment at John Hopkins. A chance encounter, a passing statement (“the color of the throat chakra is blue”), the gift of an agate.

"Look," I said, "let's take him to Chitral! There's a jeep in the baazar. Let's go." But Taleem Khana Nana said she wanted to wait for her husband to come home, surely he would be home soon and then he would come with me to take the baby. I said we should go now. I said I would pay for the jeep and the hospital. She said, "Surely he'll come. Let's wait."

For 20 years (this month!), the Center for Digital Storytelling has been supporting people in sharing meaningful stories from their lived experiences – because stories matter. Last week, Joe Lambert (our Founding Director) and I were in L.A. teaching a workshop at the Museum of Natural History. As we drove past the American Film Institute, he said, “This all started right here 20 years ago this week, at our first digital storytelling workshop hosted by AFI.”

This community-centered documentation project and virtual tour in Madaba serves as a public education tool, supports the livelihoods of Madaba residents, and provides a digital inventory of the site until the project team can return and complete its work in the museum.

Somehow, we forgot the last pandemic. The 1918 flu was conspicuously downplayed in medical records, did not fill the pages of the newspapers, and was omitted from personal journals. We cannot locate the cacophony of beleaguered voices; we will never know what they felt, what the flu did to them. There are theories as to why: it was upstaged by the horrors of WWI; it pulled the rug from under the belief in the advancement of medicine; it was too overwhelming to reiterate. Citizens, soldiers, doctors, they did not want to face it, or couldn’t. Why extend the dastardly thing’s lifespan by writing it down?

Our project wanted to create an awareness of social isolation in seniors and help move the discussion and action from isolation to social inclusion. Who better to tell people how to do this than seniors themselves?

The stories shared in the workshop break with dominant stereotypes that cast Muslims in a dark and dangerous light—showing instead the extraordinary successes, in spite of their struggles, of ordinary Muslim New Yorkers who shine in their respective professions.

As menacing as it is for the larger body-politic to malign border communities and mischaracterize them as dangerous and violent, the potential harm is even more insidious when communities that live only miles apart are separated by fear, anxiety, and mistrust. BYTE hopes through the stories to show that a child playing tennis or learning to use digital tools looks very similar, whether in Mexico or in Arizona.

Why do people tell stories? My most immediate response would be that stories connect us to each other. A good story lets a listener dive into another place and time. A good story also links a teller and a listener together by inviting that listener to imagine. The great thing about stories is that they don’t live in a vacuum. Listeners are able to imagine because they pull from their own memories and histories. This is why stories are so meaningful, because the voices of storytellers recounting a lived experience remind us all that our paths through time are the threads that weave the complex tapestry called history.

A story provides a connecting point. Data and statistics are an important part of public health, but so is storytelling. One of the elements that has been exciting about our work with StoryCenter is the opportunity to provide public health professionals with additional tools for the public education and health promotion work they do.

Once in awhile, I get a project that re-invents my commitment to the role of the arts, and storytelling, in building communities. When you have been at something for 35 years, you need those booster shots.

Last April, StoryCenter collaborated with the Palestinian Youth Movement (PYM) and the Boys and Girls Club of San Francisco on a digital storytelling workshop with a group of immigrant and refugee youth attending Mission High School in San Francisco. These young people had been organizing an all high school youth-led social justice leadership project over a period of 12 months with support from their adult allies.

"Honestly, that's the essence of Food Sovereignty: when you're growing your own food, you're controlling the production of your food, you're controlling everything about it. To me, that also ties in to land ownership.

The Lower Nine once had the highest Black home ownership rate in the entire city and one of the highest around the country, over sixty-five percent. I think the tragedy is that so many people lost not just their homes, but their property, their land. If you have land, you can build a house on it, you can grow food on it. It's yours and no one can tell you to leave.

I think we play sort of a small part in the larger picture of the food justice efforts. For me, it's very important for our community to honor positive, cultural values and the idea of self-reliance, the idea of health and close-knit community. During our programming, we've never really called out issues of Food Justice, or even really used that terminology, except with our youth interns. But it is there.

I led a training this past season that was specifically about Food Justice so the kids could understand the concepts. I feel like we're teaching the essence of Food Justice through influencing or reintegrating this idea of valuing quality food as a cultural tradition."

"In the 90's there was a discerned effort to figure out why communities, like West Oakland, were having specific elevated health issues – with assumptions food access, nutrition education, diet were correlated to ill health. So researches would come through, do these surveys and say, "Hey, you’re sick. You don't have access to healthy food." Community would be really bothered because they were like, "Obviously we know that. We live that every day" . . . After more thorough findings, there was a group of residents that asked, "Okay. This is more thorough information, but we're still talking about the problem. What are possible solutions?" This led to a planning grant to do some thinking with residents, some local agencies and other Community Based Organizations (CBO). This effort became the foundation of our work now. Our core question was, “How do we increase access to healthy food in our community, but do it in a way that also builds local economy?"

"Industrialized, globalized agriculture is a recipe for eating oil. Oil is used for the chemical fertilizers that go to pollute the soil and water. Oil is used to displace small farmers with giant tractors and combine harvesters. Oil is used to industrially process food. Oil is used for the plastic in packaging. And finally, more and more oil is used to transport food farther and father away from where it is produced.”

-Vandana Shiva, Soil Not Oil: Environmental Justice in an Age of Climate Crisis

As part of launching our Indiegogo campaign, we wanted to interview community partners about their program and perspectives on the Food Justice movement, as well ask them about to share stories of how this movement is transforming individuals within their community.

Our first interview is with Catherine “Cat” Jaffee, the Director of Communications and Public Affairs for Re:Vision International in Denver Colorado. Catherine spent her first 25 years living in Ecuador, Japan, Australia, France, the US, and Eastern Turkey. She was a National Geographic Young Explorer, a Fulbright Scholar, a Luce Fellow, and the Founder of Balyolu: the Honey Road, in Turkey’s Northeast. She worked in many countries with Ashoka, before joining Re:Vision. You can view the digital story Cat created with StoryCenter online.

The digital storytelling movement emerged from the odd cross section of community-based arts making, avant garde aesthetics, and digital media. The notion of story, and a very, very specific idea about the democratization of voice in the digital era, informed all aspects of the effort. Practitioners would use the educational process of media technology training to create a mechanism for enabling people whose stories were not being heard to make those stories visible.

That movement, having grown to thousands and thousands of supporters around the planet, gathers again next week in Massachusetts, at the Voices of Change conference. We will celebrate the enormous growth and diversity of this work with presentations from nearly 160 practitioners, researchers, organizers, and creatives, from 20 countries.

That movement, having grown to thousands and thousands of practitioners around the planet, gathers again next week in Massachusetts at the Voices of Change conference, and we will celebrate the enormous growth and diversity of this work with presentations of nearly 160 practitioners, researchers, organizers, and creatives from 20 countries.

A group of adolescents gathered at the downtown Nashville Public Library last week for a three-day Digital Storytelling Workshop to learn how to write, edit and produce a video about managing their type 1 diabetes.

The project is part of research by Shelagh Mulvaney, Ph.D., associate professor of Nursing, and her team into the design, development and testing of a Web and mobile phone-based self-care support system for this population.

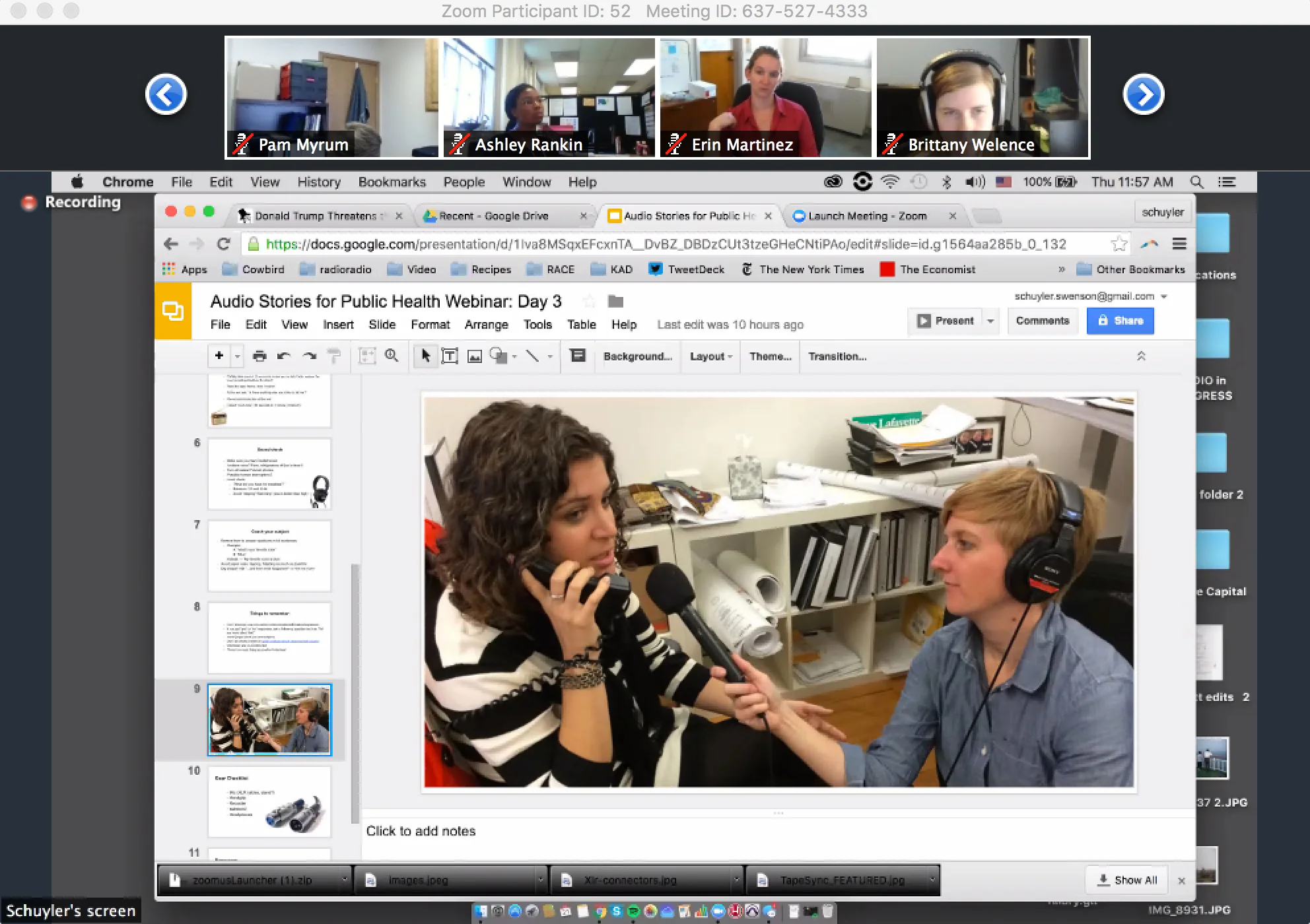

New Public Health Webinar Series

For many years, the StoryCenter has been supporting researchers and community practitioners as they explore how storytelling can enhance public health promotion. This year, we share some of our best public health strategies through a series of new, two-hour webinars.

Stories for Food Justice

We at StoryCenter are excited to share a beautiful set of academic and community stories about paths to food justice, created through a collaboration with the United States Department of Agriculture-funded Food Dignity project.

Seeding New Conversations about Sexual and Reproductive Health … in the United States and Abroad

Have you wondered when young people’s stories and voices will be taken seriously, when it comes to public conversations about sexual and reproductive health?

Grandpa Doug died a few weeks ago. He wasn’t my grandpa. He was my neighborhood’s grandpa. Always at the local elementary school being a handyman or there with his camera documenting the talent shows, the art exhibits, whatever was going on . . . even in the classes that his granddaughter wasn’t in.

We got to talking . . . and he started inviting me over for coffee. He was a coffee connoisseur, but not the kind that was snobby. He just knew a lot about it. I sheepishly asked for cream because I had heard that “real” coffee drinkers didn’t do that. He brought me cream. Happily. And we’d talk. We’d listen.

Last week, I had a beautiful birthday. I will admit that it was mostly due to Joe and his beautiful community. It is always weird to be the one entering a completely new world. Joe, in his letter about my birthday, mentioned the importance of that date for us. It is the moment that this story really began.

For me, birthdays have always been troubling. It is not because I am growing a year older. I am oddly at peace with my age, and I probably should be after it has been made public through this project everywhere. For an adoptee, a birthday is a memory of loss. It is the one day a year that you remember completely and without question that you once belonged to someone else.

Every time I'm on Facebook I notice who is having a birthday. Social media is mainly distracting, but that little convenience, being reminded about a friend's birthday, somehow balances out the distractions. It feels great to say Happy Birthday to someone every day of the year.

I believe all lives deserve a shout out, at least once a year, if not 365, by a large number of people, who simply say, it is great you exist.

Tatiana turns 42 on Wednesday, November 26. In 1972, that date was on a Sunday. I imagine myself that weekend in 1972, aware that the birth mother was preparing to have a child, perhaps she had gone into labor the day before. I had asked to be there, but perhaps the home where Tatiana was born was not so keen on the idea of the birth dad's being present, or perhaps it was decided by our parents it was not the best. I know I never saw Tatiana at birth. I wonder what that would have been like.

A couple of weeks back, I accidentally kicked my son’s twenty-five pound weight. It still hurt a couple of weeks later, so I went to a doctor. At the doctor’s office, I was given the medical form to fill out. I realized that this was the first time in forty-one years that I actually could fill out this form. I had all of the information. I briefly wondered if I should call Joe.

This is what it means to be adopted.

We are writing to invite you to become part of a journey with us: a journey to explore the story of two people finding each other across 40 years of time, to look at the issues of adoptees and their families, and to make sense of what it means to construct family in the twenty-first century.

Our names are Tatiana Beller and Joe Lambert. We are both writers and media professionals. We are both steeped in the issues of story, of life, of culture. We were both born in Texas. We both have boys, 19 years old, one Sebastian, one Massimo Sebastian, born 2 weeks apart.

Joe is Tatiana's birth father. Tatiana is Joe's biological child. Father? Daughter? The names give us trouble. We are strangers who know each other in a very peculiar, a very profound, way.

Editor’s Note: Elizabeth Peck is the Public Policy Director of the Massachusetts Alliance on Teen Pregnancy, a partner on the “Hear Our Stories” project. A partnership of the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, the Care Center, the Center for Digital Storytelling, the Civil Liberties and Public Policy Program at Hampshire College, the Massachusetts Alliance on Teen Pregnancy, the Mauricio Gastón Institute for Latino Community Development and Public Policy, and the National Latina Institute for Reproductive Health, the project aims to recalibrate the existing conversation about teen motherhood from stigmatizing young moms to promoting their sexual and reproductive health, rights, and justice.

For all the Loves that are ours, and yours, instead of chocolate or flowers,

we give you stories, and a poem.

With hearts full of gratefulness for the gifts of listening, and telling,

– StoryCenter

“I got very emotional when I read my story aloud in the first story circle before the recording. Probably it’s because November was the month when Esther passed away; this is the fifth anniversary of her death. When I said that line about the anniversary of her death, I just broke. I felt so vulnerable because I was embarrassed and then Mr. Westmoreland said, ‘Just breathe.’ That was when I was able to actually sit up and continue to read the rest of what I had written. Then when I actually did the recording, I didn’t cry. I started to get choked up toward the end, and I got choked up when Eugenia played it back. But when I actually recorded it, I didn’t cry. I’ll never forget that, when Mr. Westmoreland just said, ‘Breathe.’"

“When I told my story in our small breakout session, I got the whole point of storytelling. It’s a way to initiate conversation. That’s when other folks were asking me, ‘How is your brother a U.S. citizen, but you’re undocumented? How come your parents didn’t do it this way or that way?’ That’s when you actually sit down and have the conversation about this is how our legal system works. For example, my mother had her work sponsorship from 2001, and it wasn’t until like last year that her appeal for residency was even taken into consideration. That’s when you can talk about the 10-year backlog in our current immigration system. You can talk about what it’s like to be a youth living through that with no control of the matter. But it’s that initial storytelling that opens up that conversation.”

“I'm a Southern boy. I was born in Alabama. My dad was from Mississippi. This was in the Twenties and Thirties, and I grew up in an extremely segregated society. I ended up clearly outside—far beyond—the racial rage I was raised in as a child. I gave that up. There was something obscene about it.”

“The March on Washington: I remember my parents being very afraid for me to go. You know, thinking something was going to happen. I was kind of afraid too, but I knew that I had to do this, that it didn't matter whether I lived or died. I was going to go peaceably. I wasn't trying to fight. I wasn't going to get arrested, but I wanted to be there.”

Our All Together Now series of free civil and human rights Storied Session workshops is about bringing generations together to learn from each other what it means to stand for our rights. But it can be a challenge to make that learning reciprocal: how do you ensure that each generation feels equally welcome to listen deeply and speak truly? How can elders learn from youngers and vice versa?

Philadelphia is a long way from Elizabeth City, North Carolina, but Lisa Haynes was thrilled to make the trip this past weekend to co-facilitate the very first half-day Storied Session in our free All Together Now series of civil and human rights workshops.

To the contrary, Lisa knows how important it is to bring the generations together for these groundbreaking conversations. “The stories that were around that table,” said Lisa, “we could have been there for four days getting very significant, rich stories about their experience in Elizabeth City dealing with racism and the civil rights movement. There is such a need to talk and have exchanges. It's just so unbelievable to me how deep the well is. The older people were like, ‘Oh, I can't wait to give this website to my grandchild so they can see.’ That's what they all wanted. The younger people left that workshop that much more empowered, understanding the history of this, that this is not the first time these challenges have happened. You can't discount that sort of exchange.”

“Four little girls were killed in Birmingham yesterday. A mad, remorseful, worried community asks, ‘Who did it, who threw that bomb?’ The answer should be ‘We all did it.’ Every last one of us is condemned for that crime and the bombing before it and the ones last month, last year, a decade ago. We all did it.”

This past Sunday marked the fiftieth anniversary of another bloody and tragic Sunday, one that inspired civil rights lawyer Charles Morgan to make the speech that starts with these powerful lines. On September 15, 1963, just a couple of weeks after the massive March on Washington for Jobs and Justice, a member of the Ku Klux Klan bombed the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, killing four young girls: three 14 year-olds—Addie Mae Collins, Carole Robertson, and Cynthia Wesley—and 11 year-old Denise McNair. The bomber was initially convicted only of possessing dynamite, receiving a six-month sentence and a $100 fine. It took 14 years to bring him to justice: the case was reopened in 1971, and he was convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment in 1977.

Through this workshop, we learned more about the connection people make between stories and maps, about the process of story mapping, and also about how to use new technology and create trust and a safe space through digital communication tools.

As if by magic, by day three of the workshop, I created a digital story about resilience. Then, at the end of the workshop, a screening of all the group members’ videos occurred. It was breathtaking. What an experience! I immediately knew I wanted to do it again–someday.

Sometimes, when I think about the control that was stolen from my mother at such a young age, I want to hold her and mourn with her. But, that's not a place we can go. Sometimes, when I uncover a new scar or tenderness in my life based on what happened to me, I want to reach out to her. But, that's not a place we can go.

“Trauma. This is trauma, Katie,” I tell myself. And, just like that, I can breathe again. I feel the depth of my humanity, and of the driver’s, and it feels Incredible, to breathe it all in, and let the fear, the shame, go.

The storytelling process is not one that I had explored before with this group of colleagues, and we moved through our stories together -- first by sharing them out loud, giving them our voices, and then by creating and crafting the digital stories. Our stories centered on the broad theme of social justice and yet, they were very personal, real, clear, relatable. These were smaller acts of justice given voice by a group of nurses.

When a last minute cancellation created an opening, I found my role transformed from organizer to participant, requiring me to become vulnerable, too. I discovered StoryCenter’s process of guiding storytellers to find their “ah-ha” moment, as an art form. Common threads bound each unique story, and the bonds between participants were deepened.

After a rocky start, with plenty of naysayers breathing down my neck, I piloted the Words Beyond Bars program at Limon Correctional Facility, a vast teal and purple themed concrete and razor-wired Colorado prison complex. I sat in a circle in the visiting room with my first 12 participants wedged behind tables, with a copy of Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried and a 79-cent composition book in front of them. The men exhibited empathy, wisdom and gratitude right from the start. Slightly mystified by my energy and encouragement, they shared their own stories of the burdens they carried.

I was fed a steady diet of stories as a child, and I became them. Many were about my mother’s childhood. She emigrated from Liverpool, England in the sixties and married an American, so daughter of an immigrant has always been one of the ways I defined myself. Like her, I talked funny, held a fork differently, and felt like a stranger.

Colorado’s Medicaid Buy-In provides healthcare to 6,000 working, tax-paying adults. If the American Health Care Act is passed, the state’s Medicaid program will lose $340 million in the first year, and my friends and neighbors may be forced to move away from the communities they’ve built and into nursing homes, in order to receive the support they need.

I witnessed my own evolution, from the insecure photographer to the confident one. I saw how the chains from within were holding me back, and when other doors opened, I walked right in. I have a story, and it is being told. I really hope all women can hear it. I hope they will be braver to be what they want to be.

I went to my first StoryCenter digital storytelling workshop in August of 2014, at the old Lighthouse Writers Building in Denver. It was a summer I will not soon forget. I’d just learned of my sister’s diagnosis of stage four lung cancer, the same disease that had claimed my mother’s life barely a year before.

No big deal, I thought. As a historian, I pretty much write and tell stories for a living.

But then the story specialists at StoryCenter taught the other institute participants and I *how* to write a script for digital storytelling, and I began eyeing the door. Not because it was too big or difficult, but because it was so small and succinct. How was I going to tell a full story worth hearing in fewer than 250 words? I've probably written longer sentences than that!

February is Black History Month, and we couldn't imagine a better way to celebrate and honor it than by sharing some incredible stories from our All Together Now project on civil and human rights. With great admiration and appreciation for all the stories and storytellers in the project, we have selected a few stories to share with you here.

I was driving fast through the Ozarks when I saw Ronald McDonald sitting like a yogi on the side of the highway. I was in a hurry: I had a frequent guest discount at Deb’s Motel in Paragould, Arkansas and wanted to get there before dark. My Chevy Sprint had no air conditioner so I drove with all the windows down, blasting Depeche Mode and New Order. I was 21, working as a sales rep on straight commission covering Oklahoma, Arkansas, and northern Louisiana for a novelty show room in Dallas...

His name was Ronald. Not Ron. He made certain everyone knew that. He worked at an independent coffee shop I occasionally visited. While I admit I found Ronald cute, we had never done more than exchange small talk. That changed one hot Sunday afternoon during an open-mic poetry reading the coffee shop was hosting. I arrived late, just after he had finished serving a long line of readers and listeners. The first poet was adjusting the mic, and rather than make her compete with the whirr of the blender, I simply grabbed a bottled water out of the cooler. Ronald didn’t say a word as he rang up my drink and took my money...

What's the BackStory? You write it.

Here's how BackStory works:

Someone submits a photo, and we ask our readers to write and submit their 250-300 word BackStory – what they think the story behind the photo is... everything you can't see in the picture.

The owner of the photo, Brooke Hessler, will pick her favorite BackStory submission, and we'll post it, along with the real BackStory!

Send us your version by Monday, July 15th to: blog@storycenter.org.

I don’t have any bumperstickers on my car.

I noticed this a few years ago. Nothing… and justified it by saying that I didn’t need to share my views with anyone.

But I didn’t have any. Truth.

It was probably my dad, leaning against the oxidized green Volvo sedan, who took it. It can’t imagine it had been anyone else.

In 2005 I was part of a group who produced stories about the impact of child sexual assault through StoryCenter’s Silence Speaks initiative. Initially after viewing the stories at the end of the workshop, I felt curiosity and surprise at the immediacy of impact: I felt proud, visible, and necessary – quite different from how I had walked into the Berkeley lab feeling on the first day. What has become clear was that this process of internal re-structuring has continued to this day. Making Listening and Telling was the beginning.

Small Fists by Ryan Trauman is the first post in our BackStory series... The Story Behind the Picture.

This first BackStory is made up by someone (Trauman) who has no clue about the photo.

Here's how it works:

Someone submits a photo, and we ask our readers to write and submit their 250-300 word BackStory – what they THINK the story behind the photo is... everything you can't see in the picture.

This time, to give you an example, we asked our friend Trauman do the first one.

The owner of the photo – in this instance our very own Daniel Weinshenker – will pick his favorite submission and we'll post it, along with the REAL BackStory by Daniel.

Please email your BackStory submissions or questions to: blog@storycenter.org by May 30th for consideration.

If you have a photo that you'd like to submit to BackStory, please send it along with your BackStory script and we will consider it for a future posting.

Thanks!

– Storycenter Blog Team

I call them flower portraits.

I've been a landscape gardener in Berkeley, California for the past three years. I can't imagine living in a city without it, not just because we humans need to touch the real, live earth from time to time, but also because the plant landscape has become a surprisingly dominant feature of my urban experience. I know more about the plants I walk past every day than I know about the people inside the buildings beside those plants. I can hardly take a stroll with a friend through my neighborhood without interrupting our conversation with, "Look at that marvelous Echium over there – finally blooming!" or, "What sweet California poppies! Aren't they early this year?" (Now I even add insult to the injury of interrupting whatever my dear friend was saying by pulling out my camera and lovingly snapping a few shots of that marvelous Echium and those perfect California poppies.)

The first story I intended to write was about my father's achievements with the Alberta Métis Settlements, such as being one of the four signers to bring in the Métis accord (self governance), but as I wrote, I realized there were a lot of details I didn’t know. I wrote "Like Father Like Son" not by conscious choice, but by more of a spiritual intuition. It was something I needed to share to breathe a new light, and to explore more in depth the bond between father and son. So I drifted to something I knew deeply… the story of a boy and his hero, a story about inspiration and coming of age.

Janet, the rancher I worked for in the late 1990s, called me out of the blue last week . . . Recently I was looking at a photograph I took during that one of those calving season. Why I was looking at this photograph had nothing to do with working at the ranch, but rather to do with my work at CDS, about desire paths, about wanting to be acknowledged and feel enabled. I don’t tell Janet this, although she would have listened deeply. Instead I describe the photograph to her and in doing so tell a story. She remembers…

For 20 years (this month!), the Center for Digital Storytelling has been supporting people in sharing meaningful stories from their lived experiences – because stories matter. Last week, Joe Lambert (our Founding Director) and I were in L.A. teaching a workshop at the Museum of Natural History. As we drove past the American Film Institute, he said, “This all started right here 20 years ago this week, at our first digital storytelling workshop hosted by AFI.”

My very first interviews were exciting, and people’s reactions were better than I expected: supportive and proud. But after reading those interviews, I realized that I was leaving out important parts of my journey—mainly, the challenges I had faced.

In early September, we began exploring digital storytelling as a way to investigate the role of creative process in conflict transformation. We began with an ancient practice: sitting in a circle telling stories. We listened “inside” and “between” the stories for emerging futures that the storyteller was hungry for.

A group of adolescents gathered at the downtown Nashville Public Library last week for a three-day Digital Storytelling Workshop to learn how to write, edit and produce a video about managing their type 1 diabetes.

The project is part of research by Shelagh Mulvaney, Ph.D., associate professor of Nursing, and her team into the design, development and testing of a Web and mobile phone-based self-care support system for this population.

I think a lot about digital storytelling. That’s a given, since I work for the Center for Digital Storytelling (StoryCenter) and facilitate digital storytelling workshops. I probably ponder too much. Just ask my family and friends. I know my colleagues at StoryCenter and practitioners around the globe would agree; we’re always on about storytelling, constantly trying to provide the best workshop experience possible.

Lately my obsession has expanded from the practice and process of digital storytelling – why we make them and how they’re facilitated, to the form and function of digital stories – what they are (or can be) and how they work. It’s been refreshing and even imaginative to consider the ‘production’ of a digital story rather than merely what the story is about.

As a learner-centered college, CCD continuously strives to improve student outcomes through innovative learning techniques.

Digital Storytelling has been demonstrated to increase students' engagement and retention, and has become an invaluable tool in our arsenal.

For more than 20 years, the Center for Digital Storytelling has worked in hundreds of colleges, universities, and K-12 school districts across the United States and around the world to introduce the multimedia curricula into the classroom. Students learning Digital Storytelling come to understand the art of collaboration, shared responsibility, and accountability for their projects.

On May 8-10, more than two dozen countries were represented at the Digital Storytelling in the Time of Crisis conference hosted by the Laboratory of New Technologies in Communication, Education and the Mass Media and the University Research Institute of Applied Communication of the University of Athens with the collaboration of the Hellenic American Union.

Speakers were asked to situate their work against the backdrop of the sustained economic and social crisis of Europe and beyond. Greece has been amongst the hardest hit countries, with massive cuts in the public sector, and the decline of GDP, employment, and social programs reaching Great Depression levels. The University of Athens itself weathered a five month strike by administrators earlier in the academic year, forcing conference organizers to calibrate the conference ambitions appropriately.

Let’s be honest. An iPad, on its own, isn’t great for audio recording. The onboard microphone can’t possibly capture good quality audio, and there’s no effective way of monitoring your audio as your record it. And yet the iPad still holds some powerful allure for many digital storytellers. Believe me, I get it. The mobility. The build quality. The compact restraint of the tablet form. The tactility of the touch interface. The constant stream of fascinating new recording apps. It’s a wonder iPad audio recording hasn’t already taken off.

Enter the iTrack Solo digital audio interface from Focusrite. The iTrack Solo allows you to connect your own external microphone to your iPad and to monitor your audio input as you’re recording. What makes the iTrack Solo such a useful tool (or any external audio interface, really) is that the it does all the digital audio processing inside the unit itself before sending the audio data to the iPad.

In 2013, the Colorado Health Access Survey (CHAS) included questions around mental health for the first time. The results were significant: one out of every four Coloradans experienced one or more days of poor mental health during the past 30 days. I’m not really surprised by these findings. Nearly everyone I know, including myself, has faced at least one bout of stress, depression, or emotional instability at some point in their life.

This weekend I found myself writing a quasi-academic article about the 20 years of the work of the Center for Digital Storytelling. The argument was more or less that we have watched four significant phases in the growth of our work, each with a slightly different emphasis in our work, and in each phase an arc of expansion, a wave of interest, that surged and receded. It was an interesting way to understand what an organization, and a movement, can accomplish over two decades.

Today is Martin Luther King Day. Fifty years ago, the Civil Rights Movement changed laws and minds, securing basic rights for many, through the actions of people who did what they knew to be right. At StoryCenter, we’ve been running a project called All Together Now, collecting intergenerational stories of civil and human rights from around the country. Dr. King dreamed about a day when we would recognize each other by “the content of our character,” and storytelling allows us to do this – stories help us find out who we really are.

The CPT12 Independent Media Award honors people in our community who cultivate independent expression. The 2013 award will be presented to Daniel Weinshenker, Director of the Rocky Mountain Region Office of the Center for Digital Storytelling.

Please join us for this inaugural event. Featured speakers will include Jon Caldara of The Devils Advocate, Tamara Banks of Studio 12, Dominic Dezzutti of Colorado Inside Out, CPT12 Director of Development Shari Bernson, and CPT12 Interim GM/COO Kim Johnson.

It was rocky, far rockier than I thought it'd be. I was wanting beach.

And in the end, I did get beach. I got beach with rocks on it and I spent a whole day skipping rocks into the waves.

And it worked.

Not talking about Malta here, though that fits too. Talking about WeVideo.

For 20 years (this month!), the Center for Digital Storytelling has been supporting people in sharing meaningful stories from their lived experiences – because stories matter. Last week, Joe Lambert (our Founding Director) and I were in L.A. teaching a workshop at the Museum of Natural History. As we drove past the American Film Institute, he said, “This all started right here 20 years ago this week, at our first digital storytelling workshop hosted by AFI.”

In this world of big data and "hard" science, we lose sight of the power of a story. Stories have the power to move us, persuade us and most importantly, connect us to worlds and people beyond ourselves. As a theatre maker, I've been telling stories on stage for the last eight years, and teaching students to tell their stories for six. I've seen the impact it can have not just on the audience but on the storyteller as well.

The project involved reviewing and selecting a corpus of digital stories to be included in Aquifer. The purpose of the assignment was to help students understand the practice of storytelling by applying their knowledge of the seven steps of digital storytelling outlined by Joe Lambert to the solicitation and selection of digital stories; gain experience applying knowledge of major themes in Web 2.0 storytelling to the presentation of digital stories online; and critically engage with scholarly debates surrounding vernacular creativity, digital story curation, and assessment of digital storytelling in educational practice.

Such is the power of digital storytelling– to help people see and hear each other, across the social divides of social class, race, gender, sexual orientation, neighborhood, and religion. As participants and facilitators, we are opened to the lives and experiences of others. And we are made tender in the process.

Anxiety about technology has a long-documented history. Plato thought the act of writing was a step backward for truth. Martin Luther decried the first bound books. Leo Tolstoy criticized the printing press. The New York Times claimed that the telephone would turn us into transparent heaps of jelly. The radio was a menace; the cinema was a fad; the computer had no market; and the television was nothing more than a plywood box. The backlash is persistent.

My friend and art therapist, Dr. Paige Asawa, asked me to speak about my family’s immigration story because it represents the "little traumas," or little t’s, that can add up to big T’s, called cumulative trauma. She suggested that my family’s experience was an example of what trauma can look like over a long period time. The goal was for her students to hear the story so that they can better treat immigrant families in the future.

I still remember the feelings of inspiration and challenge I had, sitting in the audience of Show Some Skin: The Race Monologues my freshman year at Notre Dame. I was blown away by real, vulnerable, and diverse experiences of students at my own university on race, exclusion, and invisibility. Those stories challenged my own preconceived notions about how racism affects the way we move throughout the world.

For four years, the Asian Pacific Institute on Gender-Based Violence (API-GBV) has been leading the Gathering Strength project (GS), which holds an overarching theme of storytelling as it supports California’s API immigrant and refugee communities in ending violence. In August of 2016, project advisors and participants came together for 2.5 days, to strengthen and expand the GS community, honor and celebrate individual and collective accomplishments, and co-create a bold vision for the next phase of this work.

When I was seven years old, I was learning to draw by copying masterpieces. I had such confidence that I truly believed my drawings were superior. I look back on those drawings today and think “What naiveté”… and then I think, “How can I get that back?” How can I reclaim that belief in my ability to be stronger than my fear of how I might appear through others’ eyes?

Fast forward many years, and I’m sitting at my friend’s marathon poetry open mic, listening for five hours straight and never once participating. The entire time, an internal debate about whether I could or couldn’t write poetry ran through my head. I went home that night so frustrated that I chose to settle the argument by writing my first poem. The poem started like this: “You, yes You. Sitting there, just sitting there. I used to be you.” And from that moment on, the debate was over: I would not sit on the sidelines anymore; I would actively participate and learn to express my creativity. This was the start of my journey to what I call “reclaiming creative confidence.”

“I do not propose to write an ode to dejection, but to brag as lustily as chanticleer in the morning, standing on his roost, if only to wake my neighbors up.”

--Thoreau, Walden

On a trip to Cuba a decade ago to research sustainable agriculture, I arrived too late at the guest hostel in the southern, rural part of the island to see much of the hills surrounding us with palm trees in a small valley. I got my chance early the next morning when I was awoken by not one, not two, but what sounded like hundreds of roosters crowing all around me. I dressed quickly and went outside to find that roosters roamed freely in this village, strutting as lustily as Thoreau’s chanticleer. Roosters are undoubtedly more intent on alerting other roosters to their territory than on signaling transformation, but in El Valle del Gallo, as I called this place, I witnessed the power of roosters crowing in unintentional symphony at the dawn of another day.

As I was doing research for the first Sound and Story workshop , I discovered a bunch of cool resources that combine sound and story. Here are a few I wanted to share with you.

Did you miss StoryCenter's free public webinar, “How Storytelling and Participatory Media Can Support International Public Health and Human Rights Work”? Stephanie Buck of Until The Lions, a blog on the use of storytelling in international development, has written a great recap of the webinar.

One fall morning, I step outside my door and listen. I’m amazed by how many sounds I hear. A bird calls; another answers. A gaggle of school children moves left to right, full of laughter and overlapping conversation. A dog howls and a woman says to a stranger, “Sorry, she’s really into squirrels.” And how could I have ever thought there was only one wind? This morning, the wind is a pastiche of rustles, slow and fast.

Sometimes racism is so big you don't notice it. I grew up in an all white town. I didn't think about it much. It was just the way it was. It didn't mean anything. After all, we sang, "Jesus loves the little children, all the little children of the world. Red and yellow, black and white, they are precious in his sight," every Sunday. And that's what I knew about diversity. But what I didn't know then was that it was an intentional racist act that ensured that my hometown was all white. By law, black people had to be out of town by sundown. Until 1968. And that is the way it was.

STRENGHTS: Extremely Portable. Sounds fantastic. Great build quality. Cardioid pickup pattern. Device-powered.

WEAKNESSES: No headphone monitoring. Records one-person at a time. Price (though a good value).

RECOMMENDATION: For portability, durability, and sound quality, it’s a great option.

April is National Sexual Assault Awareness Month (SAAM) and National Child Abuse Prevention Month in the U.S. I remember a time when Sexual Assault Awareness Month was mostly about talking for me. As a social justice activist trying to end sexual violence, there certainly has been a lot to talk about. I can still feel the vibrations from the first Speak Out against rape that I ever attended. Indeed, it moved me to continue to tell stories of resilience and resistance. I believe stories have power. Sharing them promotes healing.

“Where are the women?” is the question behind Women’s History Month each March. The absence of women from much of recorded history and scholarship has left gaps that undermine women’s progress toward equality. While the conditions under which women’s history has been lost, erased, and suppressed may be familiar—prejudice of all sorts; sexual violence; second class status; lack of time and resources—such conditions continue to impact the inclusion of women in private and public discourse today.

February is Black History Month, and we couldn't imagine a better way to celebrate and honor it than by sharing some incredible stories from our All Together Now project on civil and human rights. With great admiration and appreciation for all the stories and storytellers in the project, we have selected a few stories to share with you here.

Can storytelling help scientists convey even complex and contentious topics like marine spatial planning?

In my experience, storytelling not only helps, it is essential if we want broader audiences to understand and support our work. Revealing something personal about why we do what we do can connect audiences with our messages and disarm adversaries.

Consider the field of marine spatial planning. Here, disconnects between scientists and audiences can be glaring.

Somewhere in a box, stored either here or there, is a framed, aerial photograph of an offshore semi-submersible drilling rig – the Ocean Ranger – being pulled out to sea just off the coast of Newfoundland. The derrick in particular, if I remember correctly, is lit soft orange by early morning sunlight and the ocean is dead calm.

Between our voices and our digital stories, there is a microphone. It’s important to get it right. If you are someone just getting your bearings as a digital storyteller, or someone who needs to buy several mics for a group of storytellers, you’ll certainly want to consider the Audio-Technica ATR2100. Not only does it sound great, but it’s also inexpensive, durable, and easy to use.

Berkeley is the kind of place where you find little surprises. As you climb down the hill from Hinkel Park in the Berkeley Hills, you may find yourself on one of the many paths that connect the streets. On the Yosemite steps there’s a wall of poems. On a walk in late January, well before dawn, I came across this poem, illuminated by the less-than-romantic light of my iPhone.

My family’s history and active involvement in the Civil Rights movement began four generations ago in Selma, Alabama where my great-grandparents and their children tended cotton fields. As a child, I heard their intergenerational stories about sharecropping, Jim Crowism, and “Daddy King” around the dinner table. My grandmother, who recently turned 92, participated in the Bloody Sunday March with John Lewis and Dr. King. In the 1970s, when Shirley Chisholm ran for president, years before there was Hilary Clinton, my mother and Ms. Shirley took me with them to voter registration events every Saturday. I don’t think I knew what voting was, but I knew Dr. King had given up his life for my right to vote. I also knew that Dr. King and his fight for black civil rights would, in many ways, define me.

I’ve been so excited about the good work being done through the All Together Now workshops across the country. Thinking back, I can’t really say I’ve had an opportunity – or I haven’t seen it – to take a stand, and to engage in the necessary civil disobedience required to go against the American grain. Even if it’s “only” telling our stories. If telling our stories is subversive to an ultimately damaging master narrative, then let our voices be like a march, and let them be heard by as many people as possible.

I grew up in Palo Alto in the '70s and '80s. I think there were three students out of a graduating class of 300 that weren't going to a 4-year college. I'm not sure I knew a single person who was joining the military. There was one publicly known homeless resident in the town, whom nobody actually believed was homeless (word around town was that he was a writer doing research for his next novel). And there were maybe ten African Americans in my entire high school.

Imagine feeling ashamed because you perpetually smell of urine or stool. Imagine mourning your stillborn baby – a baby that died because it was stuck in the birth canal and was not delivered by cesarean section in time. Imagine traveling for hours or days to reach a hospital, hoping that a doctor will be able to surgically restore your continence, which is caused by a condition called obstetric fistula. And then imagine that while you wait for your surgery date to come, you are invited to watch short videos telling the stories of women who have endured exactly the same thing as you have.

Unlike most law school students nearing the end of what can be a less than enjoyable experience, I spent my final semester living and working in the southern Caribbean region of Costa Rica. This experience was life-changing and led to the establishment of The Rich Coast Project, a community storytelling and collective history project aimed at supporting and protecting the cultural heritage of coastal Afro-Caribbean populations and other communities living along Costa Rica’s Talamanca coast.

I recently published A Bushel’s Worth: An Ecobiography, a memoir of reunion with my family’s farming traditions and a call for local farmland preservation. In the book, I alternate stories about small-scale, organic farming at Stonebridge Farm, our community-supported farm along Colorado’s Front Range, with childhood memories of my grandparents’ farms in North Dakota.

Many of the chapters in the book began as digital stories. For example, “Seeds of Never Seen Dreams” was based on a digital story I wrote about my Great-Grandma Flora, a teacher and farmer on the North Dakota prairie, and the ways I see my own life reflected in hers. The first chapter, “A Trace of Rural Roots,” began as my very first digital story, made in a Denver workshop in 2006. I had never seen a digital story before I took that workshop and had intended to write about something other than the North Dakota farms, but when I looked at childhood photos in preparation for the workshop, my heart was drawn to images of summer vacations there.

Today is Day 7 of the 11 Days of Action leading up to International Day of the Girl on October 11. This youth-led movement to advocate for girls' rights and speak out against gender bias was recognized by the United Nations General Assembly in 2011 when it adopted Resolution 66/170. This year's theme is "Innovating for Girls' Education."

In honor of this movement, and in celebration of girls everywhere, we share this story.

"We get caught up in ignoring what happened in the past. I even have people in my own family who don't like to talk about the civil rights movement because it was a very difficult time for them. It's tough for them to speak on it," said Montravias King, a senior at Elizabeth City State University in North Carolina. "But it's important that my generation know, that we be reminded of the struggles of our grandparents, our great-grandparents. That will make us more appreciative of the freedoms that we have now. And in return, when things come up that threaten our voting rights, we'll react more swiftly and say, ‘Hey! We recognize this. We've seen this before. We may not have been through it, but we recognize this, so we're not going to allow our right to vote to be taken back, to be suppressed.’"

Being on the administrative team at the Center for Digital Storytelling, my storytelling skills are rarely called upon. My creativity and relatability are spent on website maintenance and email exchange – tasks which aren't storytelling as much as they are conveying information.

Of course, my initial introduction to and love for the Center for Digital Storytelling was based on storytelling – not necessarily because I consider myself a great storyteller, but because I am a listener and an appreciator of story. In fact, for a long time I considered myself to be not a great storyteller at all. I stutter my way through sentences; I forget punchlines and other important details; I crack myself up thinking about the funny parts before I get to actually telling them. . .

Somewhere in a box, stored either here or there, is a framed, aerial photograph of an offshore semi-submersible drilling rig – the Ocean Ranger – being pulled out to sea just off the coast of Newfoundland. The derrick in particular, if I remember correctly, is lit soft orange by early morning sunlight and the ocean is dead calm.